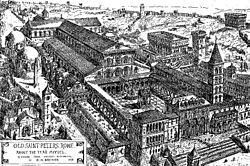

Reconstruction Drawing and Plan of Old Saint Peters

| St. Peter's Basilica | |

|---|---|

| Basilica Sancti Petri (Latin) | |

19th-century drawing of St. Peter'due south Basilica every bit it is idea to have looked around 1450. The Vatican Obelisk is on the left, still continuing on the spot where information technology was erected on the orders of the Emperor Caligula in 37 AD | |

| |

| 41°54′eight″N 12°27′12″E / 41.90222°Due north 12.45333°Eastward / 41.90222; 12.45333 Coordinates: 41°54′viii″Northward 12°27′12″Due east / 41.90222°N 12.45333°Due east / 41.90222; 12.45333 | |

| Location | Rome |

| Country | Papal States |

| Denomination | Cosmic Church building |

| History | |

| Status | Major basilica |

| Consecrated | c. 360[ citation needed ] |

| Compages | |

| Style | Early Christian |

| Groundbreaking | Between 326 (326) and 333 |

| Completed | c. 360 |

| Demolished | c. 1505 |

| Assistants | |

| Diocese | Diocese of Rome |

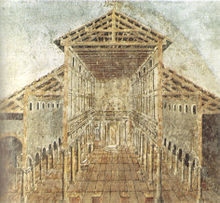

Fresco showing cutaway view of Constantine's St. Peter's Basilica as it looked in the fourth century

Old St. Peter's Basilica was the building that stood, from the 4th to 16th centuries, where the new St. Peter's Basilica stands today in Vatican City. Structure of the basilica, built over the historical site of the Circus of Nero, began during the reign of Emperor Constantine I. The name "old St. Peter'south Basilica" has been used since the structure of the current basilica to distinguish the 2 buildings.[one]

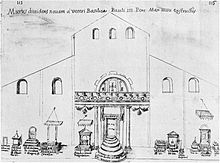

An early interpretation of the relative locations of the Circus of Nero, and the old and electric current Basilicas of St. Peter

Maarten van Heemskerck - Santa Maria della Febbre, Vatican Obelisk, Saint Peter's Basilica in construction (1532)

A map, circa 1590, by Tiberio Alfarano of the interior of Old Saint Peter's, noting the locations of the original chapels and tombs[2]

Map and location of the Necropolis in relation to (New) St. Peter's

Fontana della Pigna (1st century AD) which stood in the courtyard of the Old St. Peter'due south Basilica during the Eye Ages and and so moved again, in 1608, to a vast niche in the wall of the Vatican facing the Cortile della Pigna, located in Vatican Metropolis, in Rome, Italy.

History [edit]

Construction began by orders of the Roman Emperor Constantine I between 318 and 322,[3] and took virtually 40 years to consummate. Over the next twelve centuries, the church gradually gained importance, somewhen becoming a major place of pilgrimage in Rome.

Papal coronations were held at the basilica, and in 800, Charlemagne was crowned emperor of the Holy Roman Empire in that location. In 846, Saracens sacked and damaged the basilica.[4] The raiders seem to accept known about Rome's extraordinary treasures. Some holy—and impressive—basilicas, such equally St. Peter's Basilica, were outside the Aurelian walls, and thus easy targets. They were "filled to flood with rich liturgical vessels and with jeweled reliquaries housing all of the relics recently amassed". As a result, the raiders destroyed Saint Peter'southward tomb[five] and pillaged the holy shrine.[6] In response Pope Leo Iv built the Leonine wall and rebuilt the parts of St. Peter's that had been damaged.[7]

By the 15th century the church was falling into ruin. Discussions on repairing parts of the structure commenced upon the pope's render from Avignon. Two people involved in this reconstruction were Leon Battista Alberti and Bernardo Rossellino, who improved the apse and partially added a multi-story benediction loggia to the atrium facade, on which construction continued intermittently until the new basilica was begun. Alberti pronounced the basilica a structural anathema:

I have noticed in the basilica of St. Peter's in Rome a crass feature: an extremely long and high wall has been constructed over a continuous series of openings, with no curves to give it strength, and no buttresses to lend it support... The whole stretch of wall has been pierced by also many openings and built too high... As a result, the continual forcefulness of the wind has already displaced the wall more than 6 anxiety (1.8 thou) from the vertical; I have no doubt that eventually some... slight movement will make it collapse...[viii]

At first Pope Julius II had every intention of preserving the quondam edifice, but his attending soon turned toward trigger-happy information technology down and building a new structure. Many people of the time were shocked by the proposal, as the building represented papal continuity going back to Peter. The original altar was to exist preserved in the new structure that housed it.

Pattern [edit]

The blueprint was a typical basilica class[9] with the program and elevation resembling those of Roman basilicas and audience halls, such as the Basilica Ulpia in Trajan's Forum and Constantine'due south ain Aula Palatina at Trier, rather than the blueprint of any Greco-Roman temple.[10] The design may take been derived from the description of Solomon's Temple in 1 Kings vi.[11]

Constantine took great pains to build the basilica on the site he and Pope Sylvester I believed to be Saint Peter'due south grave, which had been marked since at to the lowest degree the 2nd century.[i] [12] This influenced the layout of the building, which was erected on the sloped Vatican Hill,[12] on the west banking company of the Tiber River.[1] Notably, since the site was outside the boundaries of the ancient city, the apse with the altar was located in the w so that the basilica's façade could be approached from Rome itself to the e. The outside, unlike earlier infidel temples, was not lavishly decorated.[1]

The church was capable of housing from iii,000 to 4,000 worshipers at i fourth dimension. Information technology consisted of five aisles, a broad cardinal nave and ii smaller aisles to each side, which were each divided by 21 marble columns, taken from earlier pagan buildings.[xiii] It was over 350 anxiety (110 m) long, built in the shape of a Latin cross, and had a gabled roof which was timbered on the interior and which stood at over 100 feet (30 m) at the center. An atrium, known as the "Garden of Paradise", stood at the entrance and had v doors which led to the body of the church building; this was a 6th-century add-on.

The chantry of Old St. Peter's Basilica used several Solomonic columns. According to tradition, Constantine took these columns from the Temple of Solomon and gave them to the church building; yet, the columns were probably from an Eastern church. When Gian Lorenzo Bernini built his baldacchino to embrace the new St. Peter'due south chantry, he drew from the twisted design of the old columns. Eight of the original columns were moved to the piers of the new St. Peter'southward.

Mosaics [edit]

The 1628 full-size copy in oil of the great Navicella mosaic by Giotto

The great Navicella mosaic (1305–1313) in the atrium is attributed to Giotto di Bondone. The giant mosaic, commissioned by Key Jacopo Stefaneschi, occupied the whole wall above the entrance arcade facing the courtyard. Information technology depicted St. Peter walking on the waters. This extraordinary work was mainly destroyed during the construction of the new St. Peter'due south in the 16th century, only fragments were preserved. Navicella means "little ship" referring to the large boat which dominated the scene, and whose sail, filled past the tempest, loomed over the horizon. Such a natural representation of a seascape was known simply from ancient works of fine art.

The nave ended with an curvation, which held a mosaic of Constantine and Saint Peter, who presented a model of the church to Christ. On the walls, each having xi windows, were frescoes of various people and scenes from both the Sometime and New Testament.[fourteen] According to combined statements by Ghiberti and Vasari, Giotto painted five frescoes of the life of Christ and various other panels, some of which Vasari said were "either destroyed or carried abroad from the quondam structure of St. Peter'south during the edifice of the new walls."[15]

The fragment of an eighth-century mosaic, the Epiphany, is one of the very rare remaining $.25 of the medieval ornamentation of Old St. Peter's Basilica. The precious fragment is kept in the sacristy of Santa Maria in Cosmedin. It proves the high artistic quality of the destroyed mosaics. Another ane, a standing madonna, is on a side chantry in the Basilica of San Marco in Florence.

-

1673 engraving showing the Navicella mosaic'due south placement on the basilica

-

Navicella mosaic - Fragment in Boville Ernica

-

Navicella mosaic - Fragment in Vatican

-

Mosaic of the Adoration of the Magi, today in Santa Maria in Cosmedin

-

Mater misericordiae, today in San Marco in Florence

-

Mosaic, today in the Museo Barracco

-

2 pairs of the original Solomonic columns at present support curved pediments to form trompe-50'œil porticoes on the piers of St. Peter's.

-

Solomonic Column

Tombs [edit]

A sketch by Giacomo Grimaldi of the interior of St. Peter's during its reconstruction, showing the temporary placement of some of the tombs.

Since the crucifixion and burial of Saint Peter in 64 Ad, the spot was thought to be the location of the tomb of Saint Peter, where there stood a small shrine. With its increasing prestige, the church building became richly decorated with statues, effects and elaborate chandeliers, and side tombs and altars were continuously added.[1]

The structure was filled with tombs and bodies of saints and popes. Basic connected to exist found in construction as late as February 1544.

The majority of these tombs were destroyed during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries demolition of Old St. Peter'southward Basilica (salve one which was destroyed during the Saracen Sack of the church building in 846). The residue were translated in part to modern St. Peter's Basilica, which stands on the site of the original basilica, and a handful of other churches of Rome.

Along with the repeated translations from the aboriginal Catacombs of Rome and two fourteenth century fires in the Archbasilica of Saint John Lateran, the rebuilding of St. Peter'south is responsible for the destruction of approximately one-half of all papal tombs. As a result, Donato Bramante, the chief architect of modern St. Peter'due south Basilica, has been remembered as Maestro Ruinante.[sixteen]

Stefaneschi Triptych [edit]

Forepart side. Tempera on forest. cm 178 × 89 (central panel); cm 168 × 83 c. (side panels); cm 45 c. × 83 c. (each section of the predella)

Back side. Tempera on woods. cm 178 × 89 (cardinal panel); cm 168 × 83 c. (side panels); cm 45 c. × 83 c. (each section of the predella)

The Stefaneschi Altarpiece is a triptych by the Italian medieval painter Giotto, deputed by Cardinal Giacomo Gaetani Stefaneschi[17] to serve as an altarpiece for one of the altars of Sometime St. Peter's Basilica in Rome.

It is a rare example in Giotto's work of a documented commission, and includes Giotto's signature, although the appointment, like about dates for Giotto, is disputed, and many scholars experience the artist'southward workshop was responsible for its execution.[18] Information technology had long been thought to have been fabricated for the chief altar of the church building; more contempo research suggests that it was placed on the "catechism's altar", located in the nave, only to the left of the huge arched opening into the transept.[nineteen] Information technology is at present at the Pinacoteca Vaticana, Rome.

Come across also [edit]

- Listing of Greco-Roman roofs

- Alphabetize of Vatican City-related articles

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b c d due east Boorsch, Suzanne (Winter 1982–1983). "The Building of the Vatican: The Papacy and Architecture". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. 40 (three): four–8.

- ^ Reardon, 2004 .p.274

- ^ Marian Moffett, Michael Fazio, Lawrence Wodehouse, A World History of Architecture, 2nd edition 2008, pp. 135

- ^ Davis, Raymond, The Lives of the Ninth-Century Popes (Liber pontificalis), (Liverpool University Printing, 1995), 96.

- ^ Partner, Peter (1972). The Lands of St. Peter: The Papal Country in the Middle Ages and the Early Renaissance, Book 10. Academy of California Printing. p. 57. ISBN9780520021815 . Retrieved 6 April 2019.

it was not at this time unusual for Muslims to desecrate Christian Churches for the sake of desecrating them, earthworks has revealed that the tomb of the campaigner was wantonly smashed

- ^ Barbara Kreutz (1996). Before the Normans: Southern Italy in the Ninth and 10th Centuries. University of Pennsylvania Printing pp. 25–28.

- ^ Rosemary Guiley, The Encyclopedia of Saints, (InfoBase Publishing, 2001), 208.

- ^ William Tronzo (2005). St. Peter's in the Vatican. Cambridge University Printing. p. 16. ISBN0-521-64096-2.

- ^ Sobocinski, Melanie Grunow (2005). Detroit and Rome. The Regents of the Univ of Michigan. p. 77. ISBN0-933691-09-2.

- ^ Garder, Helen; et al. (March 17, 2004). Gardner'due south Art Through the Ages With Infotrac. Thomas Wadsworth. p. 219. ISBN0-15-505090-vii.

- ^ De la Croix, Horst; Tansey, Richard Thou.; Kirkpatrick, Diane (1991). Gardner's Art Through the Ages (ninth ed.). Thomson/Wadsworth. p. 260. ISBN0-15-503769-2.

- ^ a b De la Croix, Horst; Tansey, Richard Grand.; Kirkpatrick, Diane (1991). Gardner'southward Fine art Through the Ages (9th ed.). Thomson/Wadsworth. p. 259. ISBN0-xv-503769-2.

- ^ Garder, Helen; et al. (March 17, 2004). Gardner'south Fine art Through the Ages With Infotrac. Thomas Wadsworth. p. 619. ISBN0-15-505090-7.

- ^ "Old Saint Peter'south Basilica." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2006.

- ^ Eimerl, Sarel (1967). The Earth of Giotto: c. 1267–1337 . et al. Fourth dimension-Life Books. p. 102. ISBN0-900658-fifteen-0.

- ^ Patetta, Federico (1943). La figura del Bramante nel "Simia" d'Andrea Guarna (in Italian). Roma: Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei.

- ^ His name is too oftentimes establish as Jacopo Caetani degli Stefaneschi.

- ^ Gardner, 57-viii, gives the documentation from the obituary book of St. Peter's. Nigh scholars date the altarpiece to c. 1320; Gardner dates it to c. 1300; Anne Mueller von den Haegen dates information technology to c. 1313; Kessler dates information technology to between 1313 and 1320.

- ^ Kempers and De Blaauw, 88-89; Kessler, 91-92.

Further reading [edit]

- The Vatican: spirit and art of Christian Rome . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art. 1982. ISBN0870993488. (pp. 51–61)

- Weitzmann, Kurt, ed., Age of spirituality: late antique and early Christian art, third to seventh century, no. 581, 1979, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, ISBN 9780870991790

External links [edit]

- The Constantinian Basilica Article by Jose Ruysschaert

- The Tomb of St Peter, book by Margherita Guarducci

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Old_St._Peter%27s_Basilica

0 Response to "Reconstruction Drawing and Plan of Old Saint Peters"

Post a Comment